Last week, the mother of a singing student asked me if the head voice was not a "wrong way to sing". In fact, this view of the head voice is not so far-fetched - it has an old tradition. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the head voice was often called "falsetto" and contrasted with the full-sounding "chest voice". Today, the word "falsetto" is distinguished from the head voice as a breathy, physically inappropriate "falsetto voice". In this blog article we ask ourselves: What is the difference between "chest voice" and "head voice", how do men's and women's voices differ here, and why is it important to train the head voice in order to be able to sing with a full voice in high registers?

With outstanding singers, it is often almost impossible to tell whether they are singing in their chest or head voice. Only modern voice science has succeeded in determining the difference between chest voice and head voice more precisely, independent of the sound. Anatomically, from the structure of our vocal apparatus, we can distinguish two basic types of vocal fold activity. The two vocal folds that produce our sounds when we speak, sing, shout etc. consist of a muscle belly. Its anatomical name is: thyroarytenoid muscle or TA muscle for short (formerly also called vocalis muscle). In the larynx, it runs from the thyroid cartilage to one of the two articular cartilages (an arytenoid) with which we bring the vocal folds together.

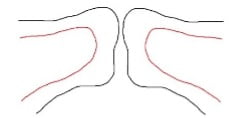

If we tense the TA muscle, the vocal cords are shortened and thickened. This makes the sound deeper and louder, for example when we speak at full voice. At the same time, the vocal folds vibrate in full width. This is why TA-dominant vocal fold activity is also called "full vibration" - that is, in the common word, the "chest voice". Here in the picture (view from the side):

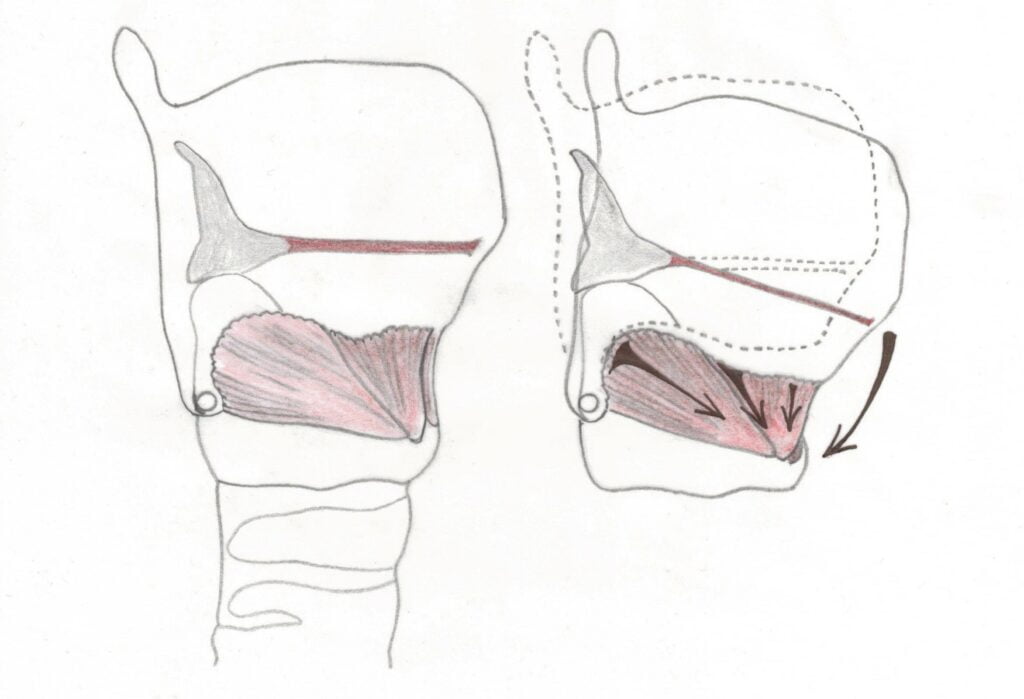

If we want to produce high tones, we have to stretch our vocal cords. We also do this with the help of a muscle, but it is an external laryngeal muscle. It runs between the thyroid cartilage and the cricoid cartilage and is therefore called the cricothyroid muscle or CT muscle for short. When we tense it, it tilts our larynx forwards and downwards and pulls our vocal cords out. This is how our tones become higher. Here in the picture:

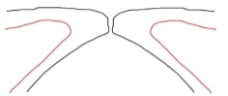

If we want to go up in pitch, we have to take some tension out of the muscle belly of our vocal folds at the same time. Then the TA muscle no longer vibrates in full width, but goes over to a marginal vibration. The vocal folds become thin and long, the tone softer - this is the "head voice". Anatomically, it is now called CT dominant vocal fold activity or "marginal vibration". Here in the picture:

As we can see, two quite different mechanisms of tone production are active here, which is why they are also called "heavy mechanism" and "light mechanism". This is important to understand because many beginners, but also advanced singers (especially male singers), struggle with a "break" or uncertain voice leading between the chest and head voice. What happens there?

When we speak, our vocal cords are short and thick - in "full vibration" mode ("chest voice" as we call it because we feel the physical resonance of the tones in the chest cavity). Over a little more than an octave (8 tones) we can speak in this mode. If we go upwards with our voice, the tonal space finally ends in which we can still speak comfortably - without feeling, for example, that we have to push the larynx upwards.

This is the point of the "first passagio", the first transition point: for tenors it is somewhere between D' and E', maximum F', for mezzo-soprano voices about F'. Men can still go beyond the first passagio for about a fourth (4 notes) with a full voice, whereby the speaking then already resembles a strained shout. After that, one reaches a point where one can no longer rise higher with a full voice - the voice drops or it breaks and rolls over into the head voice, not infrequently into the thin falsetto mentioned at the beginning. This "second passagio" is between G' and A' for tenors, and much higher for mezzo-sopranos, around D'' to E''.

Between these two points is the passagio area, the transition area between the chest voice and the head voice. Here we can switch back and forth between chest and head voice. It can be helpful and fun to playfully jump back and forth between the chest and head registers, as in a cheering "Woo-hoo! (or when yodelling. For example, as Elvis Presley does here with the Sweet Inspirations during a rehearsal break:

But above all, the passenger range is the tonal space in which our middle voice or "mixed voice" lies. With the "mixed voice" we can create gradual transitions between chest and head voice without our audience hearing a break. For example, if we sing with a speaking quality in our full voice and want to transition seamlessly from here upwards into the head voice, we have to become quieter: In this way, we gradually take the tension out of our vocal muscle (the TA muscle), which shortens our vocal cords; then, with the help of the laryngeal tilt function (the CT), we can lengthen our vocal cords to sing higher notes. And conversely, we can move from the higher, rim-voiced head voice position to the speaking-voice-like full vibration by gradually adding more TA muscle tension again - or "mixing in", as the name "mixed voice" suggests.

The mix between full and edge vibration also opens our singing voice upwards. The good news is: even in higher registers we can sing with full vibration without damaging our voice. This will "BeltingThis is called "full-voiced singing with high TA muscle activity, balanced with a strong, secured CT function. But this also means that in order to sing in high registers with a full voice, we must have a trained head voice. Without balancing with the head voice function, we just push our chest voice up and roar or bark - and become hoarse. We get an idea of this balance when we look into this little demonstration by Pavarotti, which is commented on by the American singing teacher Seth Riggs:

In popular singing, other functions become important when belted, including the "Twang", through which we can "boost" the carrying capacity of our singing in a way that is easy on the voice.

When it comes to mixing chest voice and head voice, there is a difference between men and women. You may have heard it from others or noticed it in yourself: men usually find the transition between chest and head voice more difficult than women. The reason for this can be traced back to the different Growth of the larynx during puberty back. Due to testosterone, the larynx of boys grows by about 40 % during puberty, and at the same time the vocal folds become larger and thicker, resulting in a voice that is about an octave (8 tones) lower. Externally, this is recognisable by the so-called "Adam's apple", the protruding thyroid cartilage of the adult male. The larynx of girls also grows during puberty, but to a much lesser extent. At the end, their voice is about a third (3 tones) lower.

The growth in size of the larynx in such a short time leads in boys to a temporary loss of muscular balance between the chest and head voice (TA and CT) - audible as a croaky or brittle voice, also in the uncertain fluctuation between high and low notes. This is the notorious "voice break" that still affects many men in their adult years. Unlike women, they have to completely rebuild the functional balance of their voice after puberty. This has a particular effect on the demanding transition between the chest and head voice: Because their vocal folds are larger and thicker than those of women, they have to shift more mass around in order to change from full to marginal vibration and back again. To manage this without an audible break, aspiring singers need different vocal pedagogical support than female singers.

Unless they prefer yodelling. Because in the end only one thing counts: Have fun singing!

You can find great exercises for building your voice and the seamless transition between chest and head voice in my Online singing courses.

I look forward to seeing you,